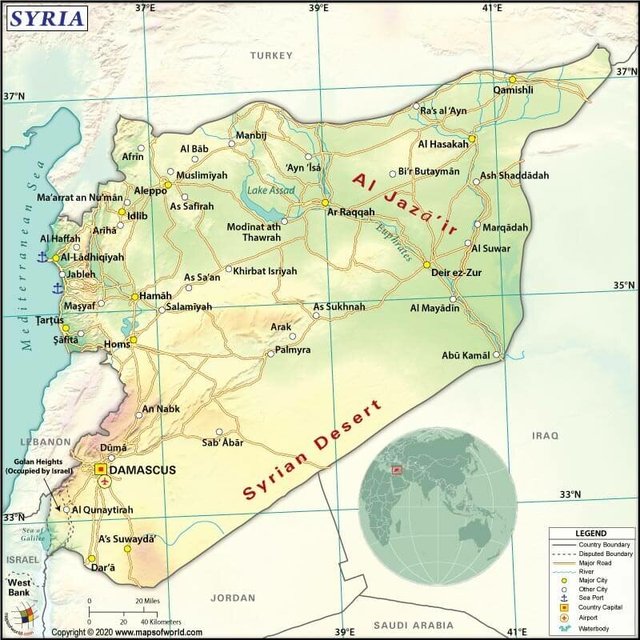

Palmyra named by the Romans "place of palms" is located in an oasis in the Syrian desert midway between the Mediterranean and the Euphrates. In the Bible and ancient Assyrian texts it was called Tadmor which is its modern name today.

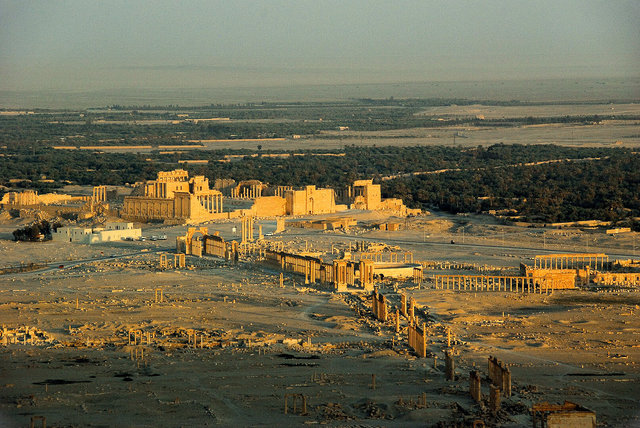

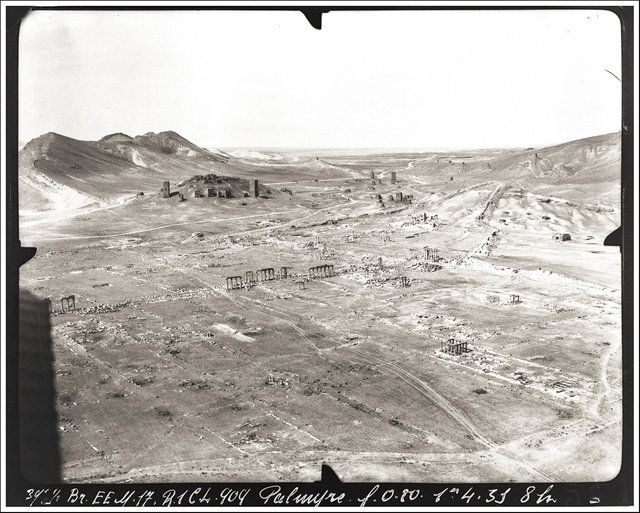

Fed by a spring, the walled city was bordered by date palms and olives on one side and high hills on the other. At its peak it is thought to have had a population of over 100,000. Its inner defensive walls enclose about 200 acres, rivaling in size the old city of Damascus. (View from the nearby Mamluke Castle)

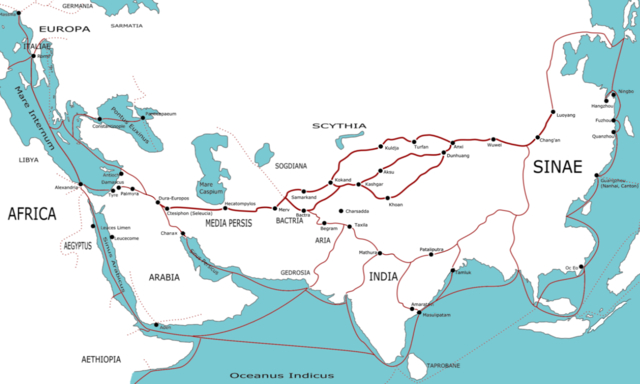

How could so wealthy a city be built in the middle of a trackless desert. The answer lay in its location on a trade route between Mediterranean ports in the West and the silk road in the East. Palmyra was a way station and trading entrepot providing food, water and armed protection to camel caravans for a fee.

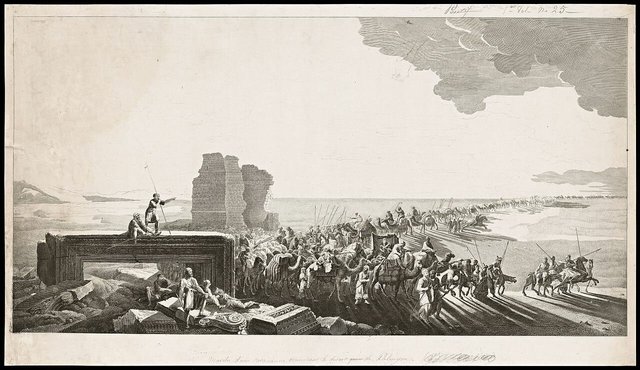

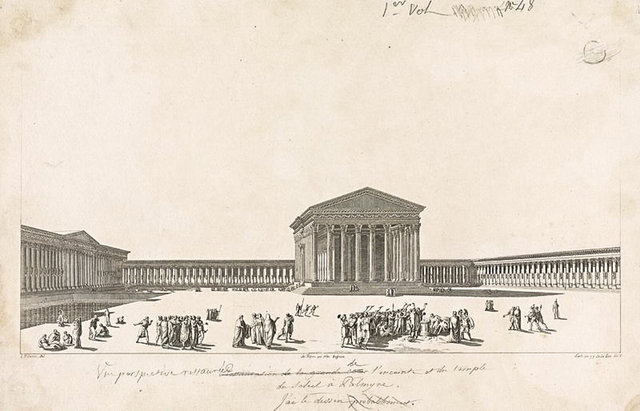

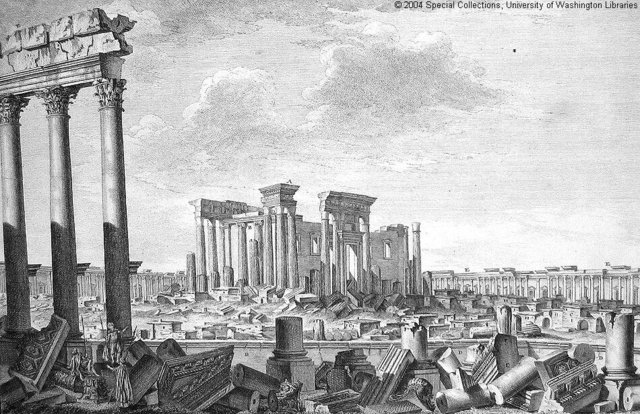

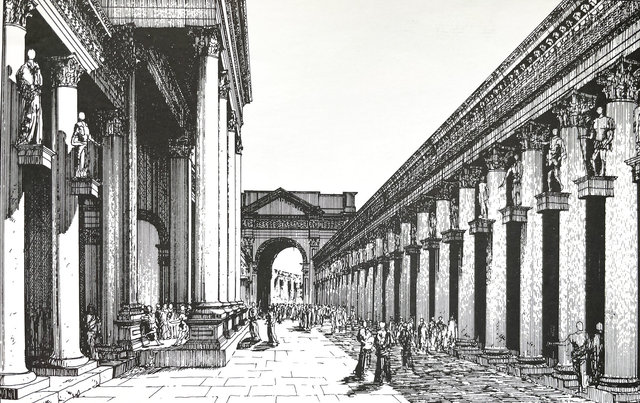

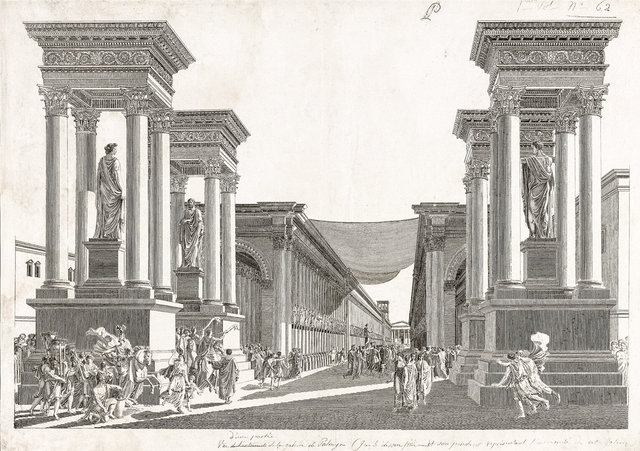

Up to 1,000 camels and pack animals might make up a caravan from Dura-Europos on the Euphrates to Palmyra, then on to the Mediterranean. (Engraving inspired by Louis-Francois Cassas' visit in 1799.)

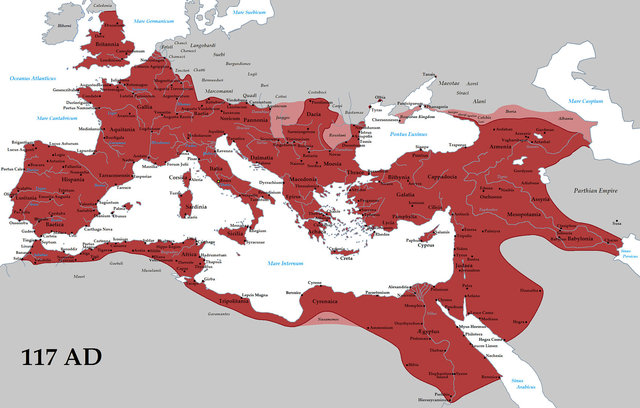

The Roman Empire at its peak under Hadrian with Palmyra as a major allied power in its eastern Province of Syria. Palmyra's autonomous authority under Rome came to an end when, during a period of Roman weakness in 273 AD, Queen Zenobia defied Roman authority and took control of its Eastern territories from Egypt to southern Anatolia. Zenobia's independence lasted only two years.

The French built the Zenobia Hotel next to Palmyra's ruins in the 1920s. Previously tourists stayed in tents after days of slow travel across the desert. The 1912 Baedeker advised visitors to travel with an armed escort. (Photo BGB 1996)

The Zenobia was full so this was my second best in the town of Tadmor. Whether this Vespa actually visited all the countries advertised is a question. (Photo BGB 1996)

The Temple of Bel (the Semitic god Baal) was certainly the most important religious building of the 1st century in the whole of the Middle East. Dedicated in 32 AD, the temple stands inside an enormous walled compound each of whose four sides is over 670 feet long. (Photo BGB 1996)

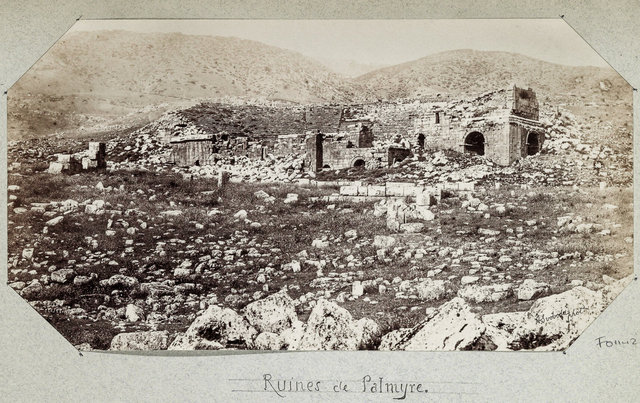

The earliest visual record of Palmyra in the West. Painted by G. Hofstede van Essen in 1693 from sketches he made on site with the English expedition from Aleppo in 1691. More sketches would not be made until 1751.

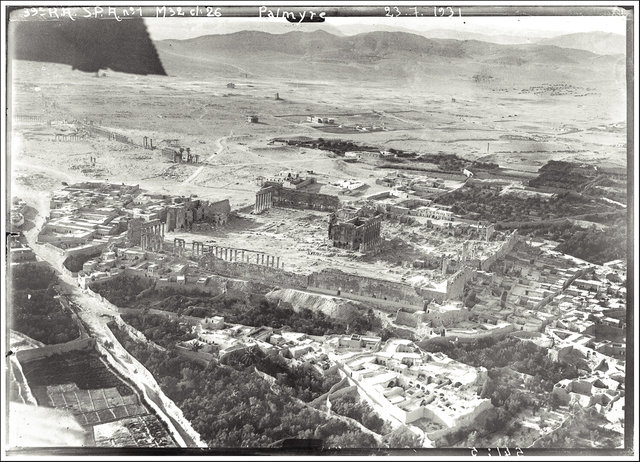

The Temple precinct was fully occupied by a mud brick village in the 1920s enjoying defenses provided by temple walls 50 feet high. The villagers were paid by French archaeologists to relocate outside the walls in the 1920's.

Inside the temple precinct before the clearance. (Photo by John Garstang/1920s.)

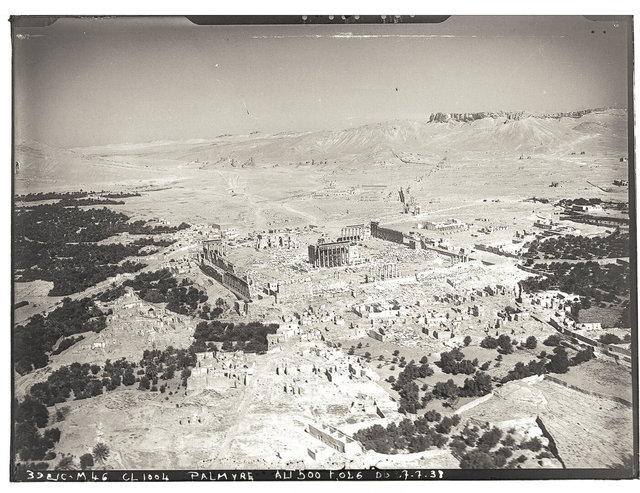

VIew of the city and its vast temple in 1938 after the clearing of mud brick houses,

This is one of 29 glass plate negatives, the first photographs of Palmyra, made by by Louis Vigne in 1864. This is the northwest corner of the precinct of the Temple of Bel.

The same northwest corner of the Temple enclosure in 1996. Here is the best preserved section of the outer wall with pedimented windows. An arched tunnel under the columns formed the entrance for sacrificial animals. (Photo BGB 1996)

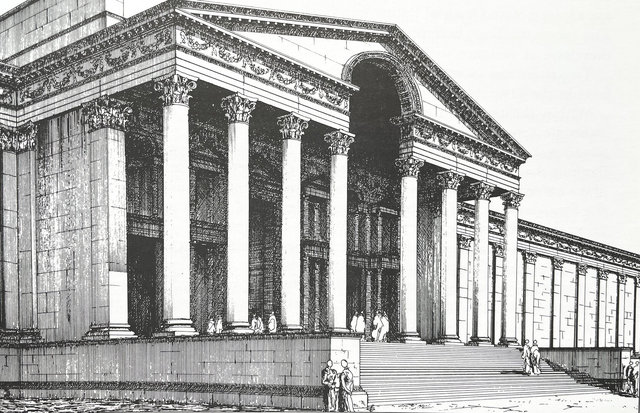

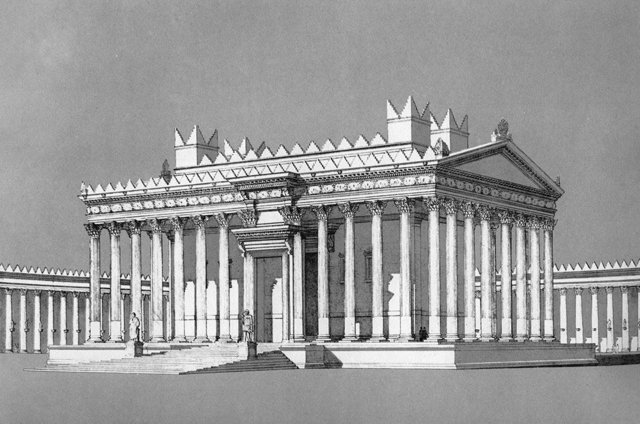

Engraving after drawing by Louis-Francois Cassas in 1799, with his reconstruction of the precinct of the Temple of Bel as it appeared in 120 AD.This enclosure was more than 2-1/2 times the area enclosed by the Jupiter Temple in Damascus. Here the Hellenistic details are paramount.

The southwest corner of the temple precinct with some of the fluted columns that once made up the Cella colonnade. The walls behind are thought to have been damaged by an earthquake and then roughly reassembled in medieval times. (Photo BGB 1996)

The same southwest corner from the outside looking in. (Louis Vigne 1864.)

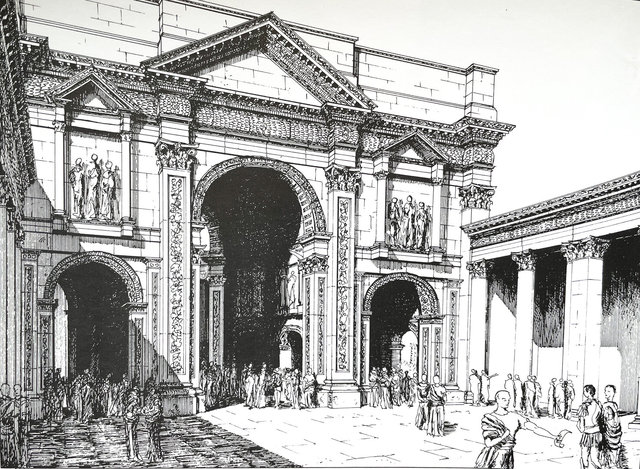

An imaginative recreation of the impressive entrance porch through the Temple perimeter wall, now lost and replaced by an Ottoman citadel entrance . (Drawing by Iain Browning 1979.)

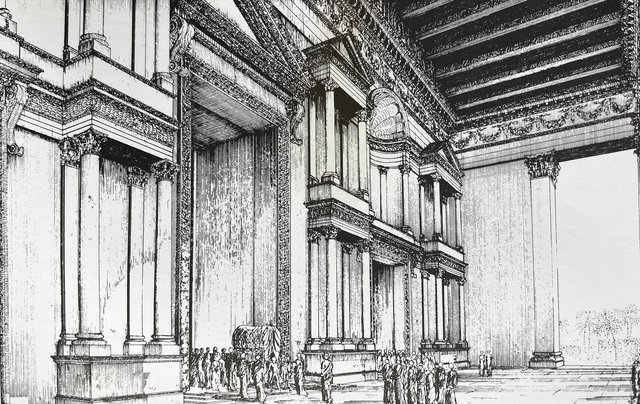

Under the porch (the Propylaeum) entering the Temple precinct. This monumental entrance is thought to date from the late 2nd C.

Through the porch, looking back at a religious procession returning a cult idol to its sanctuary. The western portico wall was taller with one row of columns rather than two as elsewhere.

The Temple of Bel from the air in 1931. Ba'al, translated as "the Lord Master" was particularly associated with the storm and fertility god Hadad and his local manifestations. From the land of Canaan, Baal was spread to Egypt and around the Mediterranean by the Phoenicians.

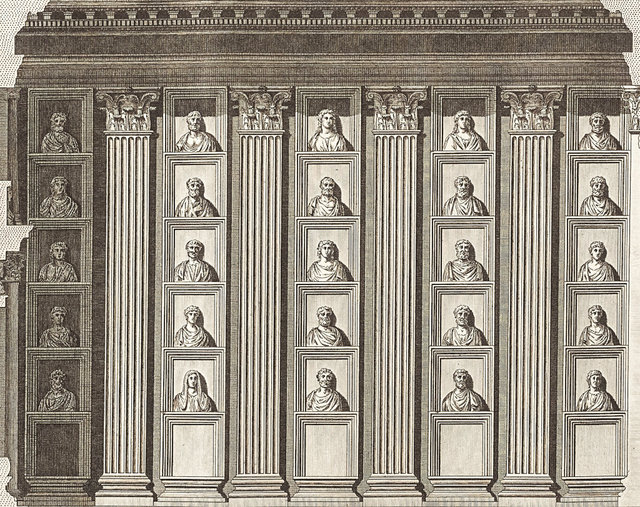

On a podium in the middle of the court was the actual temple building, the Cella, here depicted in an engraving of 1753, from a drawing by Giovanni Borra

The same view from the east as the Borra engraving but missing three columns. On the plaza to the left of the Cella was an open air altar for the ritual sacrifice of animals including bulls and camels. (Photo /the BBC)

Palmyrene art and architecture was less a direct Roman transplant and more of a synthesis of Hellenistic, Parhian and Semitic traditions that preceded the arrival of Rome.

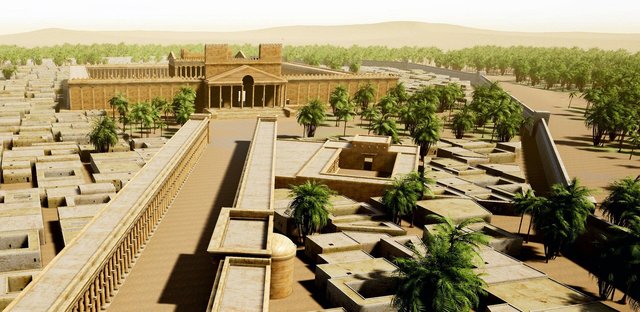

This reimagining of the Temple has greater emphasis on its Mesopotamian details, including roof structures for burnt offerings. (Visualization after Robert Amy. from Henri Seyrig, Robert Amy, and Ernest Will, Le Temple de Bêl à Palmyre (Paris: Librairie orientaliste Paul Geuthner, 1975),

The east wall of the Cella in 1996. Instead of the Corinthian capitals seen around the courtyard peristyle these columns are thought to have had bronze capitals. (Photo BGB 1996)

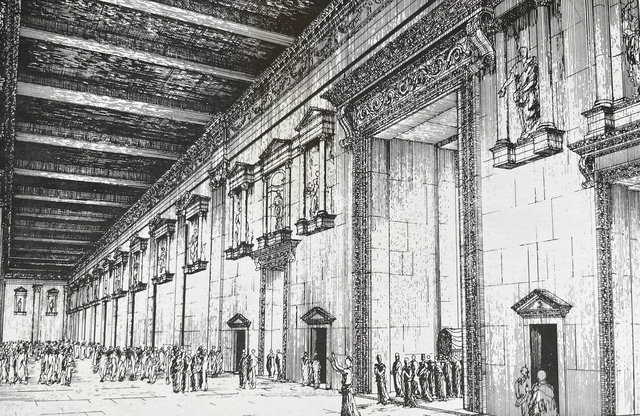

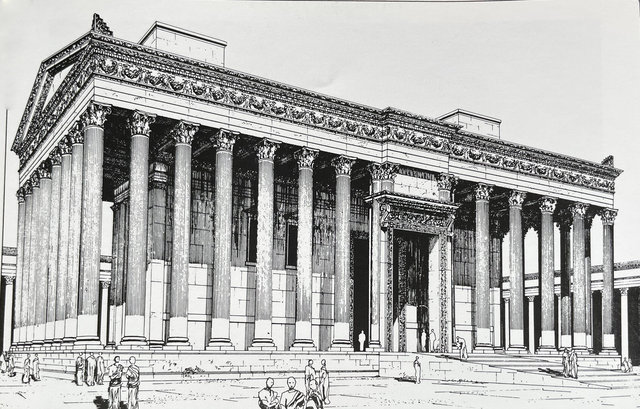

This reconstruction of the Cella shows what the bronze capitals might have looked like. The columns are 50 feet high vs. those of the Parthenon which are 34 feet high. The main entrance is off center on the side rather than on the end as in the Greek and Roman tradition.

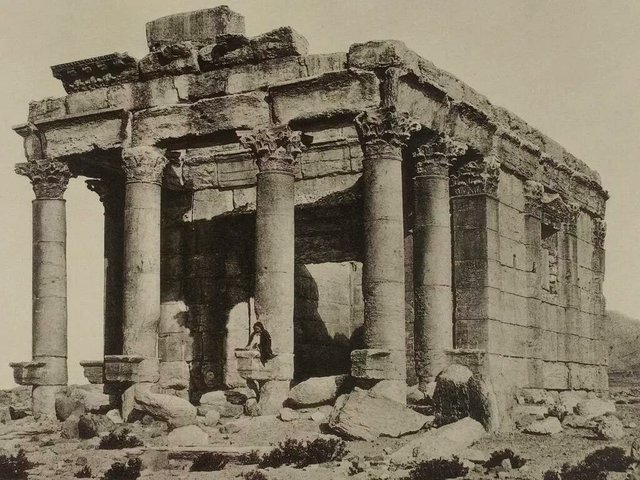

This is the Temple of Bacchus at Baalbek in the Bekaa Valley of Lebanon dating from the end of the 2nd C. Its columns are 66 ft high. Unlike Palmyra, Rome commissioned this temple which is only 45 miles from Damascus. What does it owe to the older Temple?

Entrance to The Temple of Bacchus in Baalbek (photo by Felix Bonfils, 1870-1885)

Entrance to the Cella of the Temple of Bel which similarly dwarfs human scale. (Photo BGB 1996.) This monumental gateway owes more to Egypt than to classical Greek forms. (Photo BGB 1996)

The Cella was unique in the fact that it had two inner sanctuaries, north and south which housed the cult statues of Bel and other local deities. I am standing in the south sanctuary looking north, with a bit of the famous coffered ceiling above me. (Photo BGB 1996)

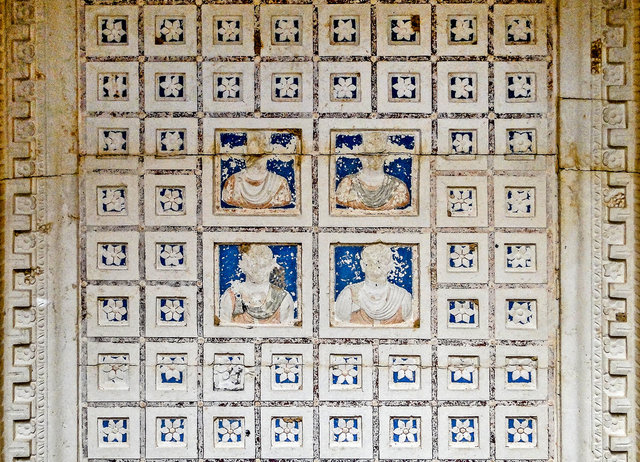

The north, more important sanctuary chamber has a coffered ceiling showing the signs of zodiac. It had no steps and housed images of the Palmyrene triad of Bell and the gods of the sun and moon. (Photo BGB 1996)

The divine triad of Palmyrene gods Baalshamin, Aglibol, Malakbel in Roman military garb. Roman, 1st century CE. Limestone. Excavated outside the city. (The Louvre, photo: Hervé Lewandowski.

The southern sanctuary with its steps probably housed the portable image of Bel that could be carried around on feast days. The Greeks and Romans put their gods on pedestals. The idea of putting their idols in tabernacles is Syrian. (Photo BGB 1996)

The glory of the south sanctuary is the monolith ceiling that so excited Wood and Dawkins in 1751. (Photo BGB 1996)

This huge painting in the National Gallery of Scotland celebrates Robert Wood and James Dawkins, two English antiquarians who with an Italian draftsman, Giovanni Borra, spent two weeks in Palmyra in 1751. Their careful drawings of architectural details and ruined buildings were published as engravings in the famous two volumes, "The Ruins of Palmyra" which had an enormous impact on designers and architects in England in the 1750's.

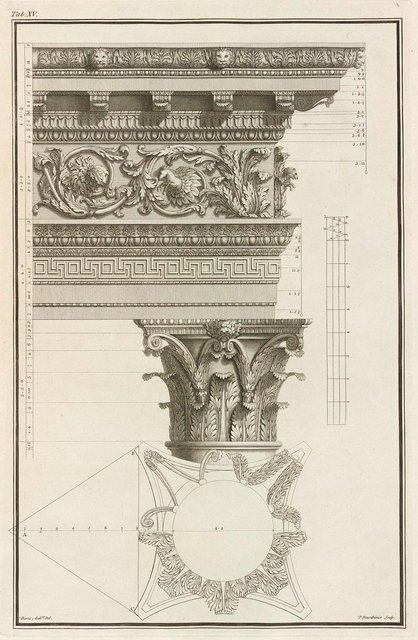

Decorative detail, one of 100 plates from the two volume "Ruins of Palmyra, otherwise Tedmor, in the desart (London 1753.) The first publication to include not only views of the ruins, but also architectural details that greatly influenced neoclassical architecture in Britain, Europe and America.

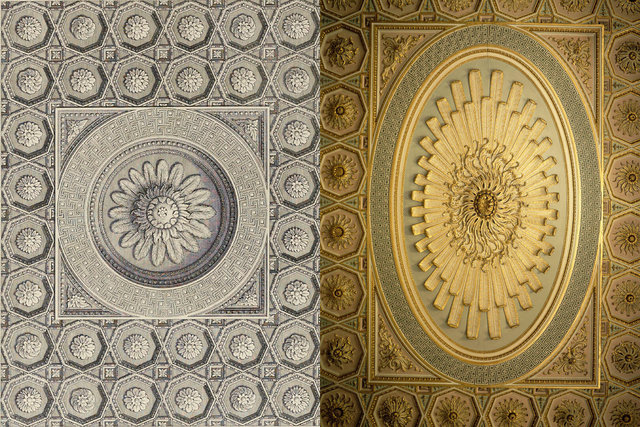

North Adyton ceiling from The Ruins of Palmyra by Robert Wood. (after drawing by Giovanni Battista Borra.) Robert Adam ceiling of 1772 at Osterley Park in west London. By the end of the century there were more than 30 "Palmyrene ceilings" in England.

Beautiful carved detail lying loose beside the Cella. (Photo BGB 1996)

The Cella of the Temple was blown to bits by ISIS in August of 2015 ending the 2000 year life of the best preserved early Semitic temple in the Middle East. (Image analysis: Unitar-unosat)

In addition to their destruction of Palmyrene monuments, ISIS also beheaded the Director of Antiquities in Palmyra, Khalid al-Asad during their year-long occupation in 2015. (photo 2021/ Louai Beshara/AFP.)

A simplified contemporary reimagining of the Temple of Bel and the Colonnade Street at its eastern terminus.

A view back toward the Temple from the Exedra, a semi-circular indentation in the line of columns connecting the late 2rd C. public entrance of the Bel Temple to the Monumental Arch on the left.

Another view of the Exedra which included seating and niches celebrating honored citizens. (Photo BGB 1996)

The Monumental Gate marks a 30 degree turn in the broad avenue from the Bel Temple into the grand Colonnade street. This depiction of the Gate was included in Robert Wood's famous volumes of 1753.

Louis Vigne's glass plate of 1864 shows only a little degrading of the gate from the 1751 depiction.

The Gate as it appeared in 1996, almost unchanged from 1864 but for the addition of some supporting stone blocks part of a 1930s restoration. (Photo BGB 1996)

This structure has excited many visitors as it is really a pair of elaborately decorated gates that pivot like a hinge 30 degrees to anchor the end points of two avenue lines of sight. (Photo BGB 1996)

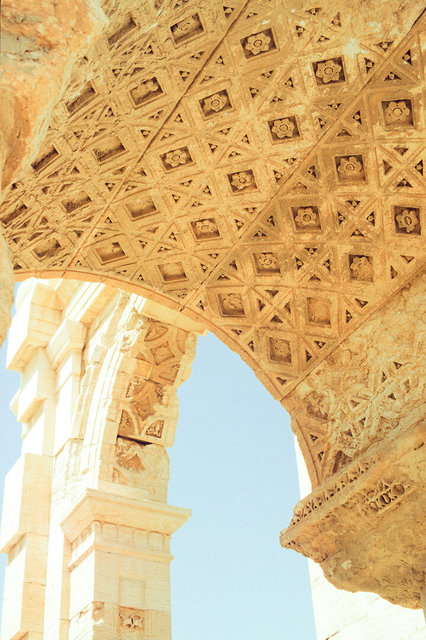

The geometric decoration so abundant around Palmyra was a source of inspiration for the 18th C. neo-classical revival celebrated by English taste-makers such as Horace Walpole and Robert Adam. (Photo BGB 1996)

More decorative detail under the Monumental Arch. Similar decorative motifs can be seen on other arches built during the reign of Septimius Severus, such as in Leptis Magna on the Libyan coast.(Photo BGB 1996)

Recreation of the Monumental Gate by Iain Browning - 1979. Its scale in relation to the towns people seems a little exaggerated.

However, this image with figures in the foreground suggests the scale of the Monumental Arch in the previous drawing is actually pretty accurate. This would be s principal entry point for camel caravans entering the city. (Photo BGB 1996)

The monumental Arch, built around 200 AD was dynamited by ISS during their first occupation in October 2015.

Remains of the Monumental Arch - April 2016 soon after recapture from Isis. (credit New York Times.)

View back to the Monumental Arch with the entrance to the Baths of Diocletian on the left. This section of the Colonnade Street is mid-to-late 2nd C. (Drawing by Iain Browning 1979.)

On the left is the entrance porch to the baths of Diocletian marked by red granite columns brought from Egypt. (Photo BGB 1996)

The central colonnade street as depicted by Wood in 1751. Behind the columns were shops and side streets the Agora, municipal buildings and private dwellings.The center of the street was not paved to make it easier for camels. The 18th C. English were not happy about the statue brackets and depicted them at a more aesthetically pleasing height.

The grand colonnade street, 7/10ths of a mile long, with covered side passages, and cross streets, together with its major public buildings, is an outstanding illustration of urban design at the peak of Rome's engagement with the East. This same view showing the brackets as they actually are. (Photo BGB 1996)

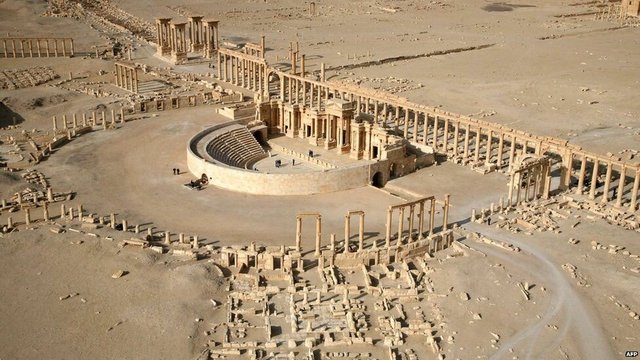

The Roman era theater, with entrances directly off the main colonnade, was mostly buried by the desert in the 19th C.

This aerial shows the theater partly restored. (the BBC/AFP)

The theater stage as it appeared in 1996. Capitals and pediments were restored on new columns in the 1950s. (Photo BGB 1996)

Another view of the stage facade in 1996. (Photo BGB 1996)

The pediment and crown over the central entrance to the stage. (Photo BGB 1996)

ISIS propagandists used the stage as a backdrop for executions of captured government troops in 2015. The pediment over the center entrance was destroyed by ISIS during their second 3-month occupation of the city in early 2017. (Getty Images.)

The Temple of Baal-Shamin, another rain god in the Semitic pantheon.The earliest section dates from 17 AD. Private donors added to it in the early 2nd C with final improvents during the time of Zenobia. The Swiss made significant restorations in the mid-50s.

The Temple of Baal-Shamin (circa 1900) by Theodor Wiegand (Berlin 1932).

The small Cella of the temple precinct dates from AD 130 immediately after the Roman Emperor Hadrian's visit to the city.(photo: Jerzy Strzelecki 2007-Wikimedia)

ISIS released this propaganda photo of their dynamiting of the temple of Bal- Shamin in August 2015.

Elegant fragments of ruined buildings lie scattered about much as they did in the 18th C. (Photo BGB 1996)

Remains of the inner peristyle of a grand private house. (Photo BGB 1996)

The Tetrapylon is one of the most recognizable of Palmyrene monuments. Restored by the French.,it was originally built to anchor one end of the great Colonnade street opposite the Monumental Arch. Each structure sheltered a more than life size statue. (Photo BGB 1996)

Recreation of the Tetrapylon and Colonnade Street. By an anonymous artist after Louis-Francois Cassas a French architect who made many architectural drawings of Palmyra published in 1799.

Another view of the Tetrapylon at dusk. (Photo BGB 1996)

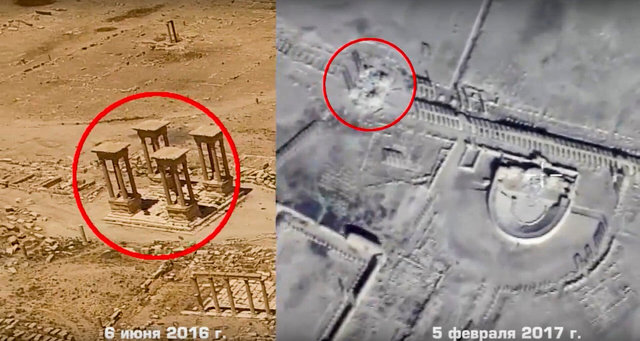

Russian photographs of the Tetrapylon after the first recapture from ISIS in early 2016, followed by a view of its destruction after the second ISIS occupation in 2017.

The Tetrapylon destroyed as it appeared in 2017.

(Photo BGB 1996)

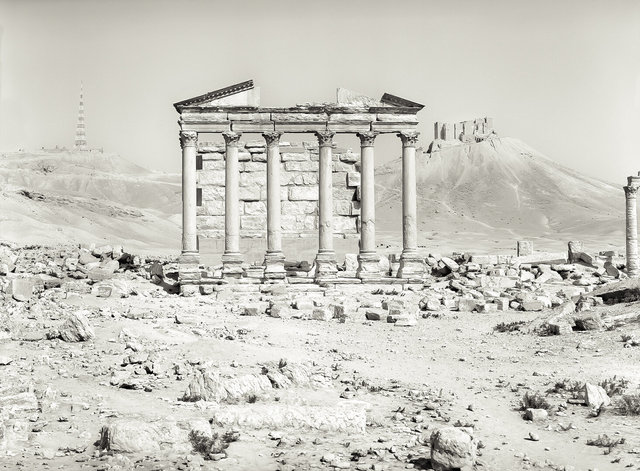

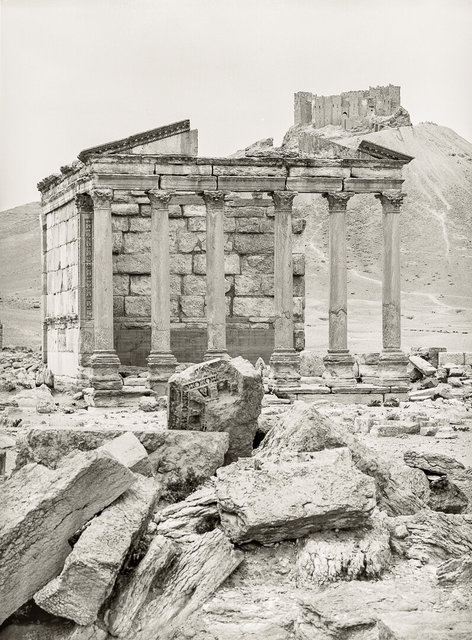

The Greco-Roman Funerary Temple is the focal point and terminus of the great Colonnade Street. The Mamluk castle in the distance dates from the 13th C. (Photo BGB 1996)

Another view of the Funerary Temple. (Photo BGB 1996)

A reconstruction of the intersection of the Colonnade Street and the Funerary Temple. (Ian Browning 1979.)

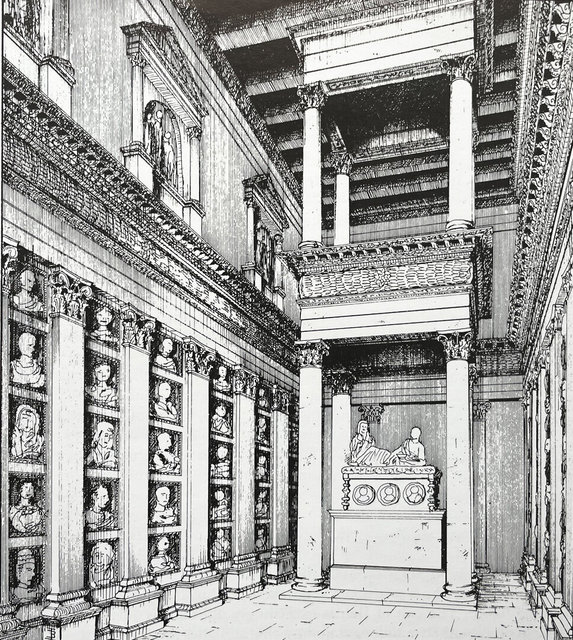

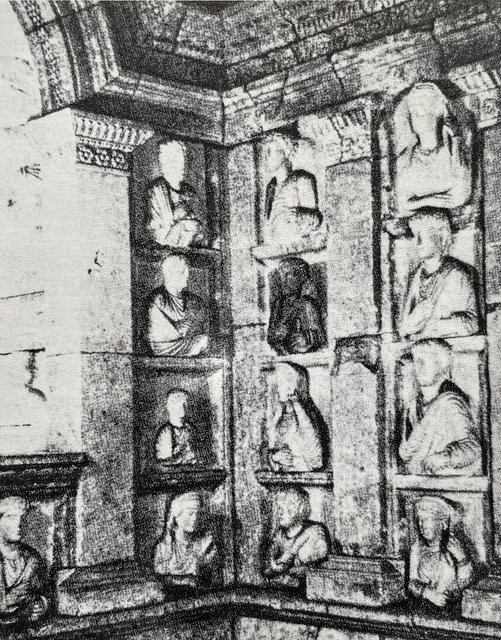

The imagined interior of the Funerary Temple with carved reliefs sealing each burial niche,"a veritable family portrait gallery." (Iain Browning 1979.)

Behind the Funerary temple is the 13th C. Mamluke castle. (Photo BGB 1996)

Looking back from the Funerary Temple toward the Tetrapylon. (Photo BGB 1996)

The same view from a wider angle back toward the Tetrapylon. (Photo BGB 1996)

A View toward the Valley of the Tombs, This government photograph dated 1931 traces the boundaries of the city and its walls.

Long lens view from above The Tower Tomb of Kithoth looking back toward Palmyra.

The Valley of the Tombs where wealthy families buried their dead. This photo gives a good idea of the desolate landscape surrounding the oasis. While walking here I had to shelter from a sandstorm. (Photo by Vyacheslav Argenberg - 2008)

There are the remains of as many as 500 tombs in the Valley.

Two hypogea entrances with looted sculpted sarcophagi. These underground family burial chambers typically had multiple rooms with burial niches. Late 1st C. (Photo BGB 1996)

Ruined tower tomb with the Mamluke castle in the background. (Photo BGB 1996)

The early tower tomb of Kithoth dating from 40 AD around the same time as the first phase of the Temple of Bel. Destroyed by ISIS in August 2015. (Photo BGB 1996)

Kithoths tower tomb as it appeared in 1864. The earliest examples of painting on plaster were found inside this tomb.

The same tower tomb of Kithoth in the foreground in 1996. Across the valley on the left is the tower tomb of Iamblichus of 81 AD. It was the first of dressed stone and held 200 burials over three floors with impressive interior cornices and pilasters. Both towers were blown up by Isis in 2015. (Photo BGB 1996)

Some tower tombs held hundreds of embalmed bodies, each in a niche sealed with a portrait of the deceased. This is the recreation of a Palmyrene tomb in the Museum in Damascus.There are some 3,000 tomb portraits scattered across museums worldwide.

The four-story sandstone Tower Tomb of Elahbel completed in 103 AD. An internal staircase led to the roof. (Photo by Vyacheslav Argenberg 2008).

Main chamber of the Tomb of Elahbel. Fragments of silk from China were discovered in a sarcophagus here.

Ceiling detail of the tomb of Elahbel. By the end of their second occupation Isis had dynamited this, and all eight of the most elaborate Palmyrene tower tombs.

Wall with burial niches, Tomb of Elahbel. (from Louis-François Cassas, Voyage pittoresque de la Syrie, de la Phoenicie, de la Palaestine et de la Basse Aegypte, vol. 1 (1799–1800).

Modeling Greco-Roman naturalistic traditions of portraiture, but often draped in native Parthian garments with eyebrows more stylized and incised, as in the Assyrian tradition. (British Museum.)

The marble cult statue of the Arabian goddess Al-Lat excavated from her temple in Palmyra. This Hellenistic sculpture takes much from representations of the Greek Athena with whom this goddess was associated. The head and arm were smashed by ISIS. (Palmyra Museum)

Funerary bust of a Palmyrene priest of around 230 AD. The largest collection of 100 funerary portraits collected by Danish archeologists since the 18th C. is in a Copenhagen museum.

Funerary bust of a wealthy Palmyrene lady in the Copenhagen Museum.

The same bust after a digital recreation of how it might have looked 1800 years ago based trace pigment analysis.

A grand family grouping from a tower tomb in the Palmyra Museum.

The same sculpture showing the kind of damage done to a majority of the major items in the Palmyra Museum.

20-foot replica of the Monumental Arch carved in Italy based on designs by the Institute of Digital Archeology at Oxford. The arch traveled to London, Geneva, Florence, and New York. Efforts are already underway to work out how best to restore at least some of the monuments destroyed by ISIS.